Our mercenaries in Iraq

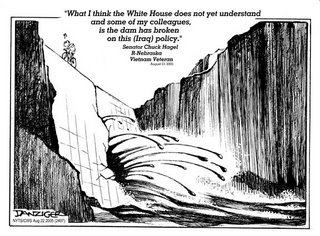

The president relies on thousands of private soldiers with little oversight, a disturbing example of the military-industrial complex.

AS PRESIDENT BUSH took the podium to deliver his State of the Union address Tuesday, there were five American families receiving news that has become all too common: Their loved ones had been killed in Iraq. But in this case, the slain were neither "civilians," as the news reports proclaimed, nor were they U.S. soldiers. They were highly trained mercenaries deployed to Iraq by a secretive private military company based in North Carolina — Blackwater USA.

The company made headlines in early 2004 when four of its troops were ambushed and burned in the Sunni hotbed of Fallouja — two charred, lifeless bodies left to dangle for hours from a bridge. That incident marked a turning point in the war, sparked multiple U.S. sieges of Fallouja and helped fuel the Iraqi resistance that haunts the occupation to this day.

Now, Blackwater is back in the news, providing a reminder of just how privatized the war has become. On Tuesday, one of the company's helicopters was brought down in one of Baghdad's most violent areas. The men who were killed were providing diplomatic security under Blackwater's $300-million State Department contract, which dates to 2003 and the company's initial no-bid contract to guard administrator L. Paul Bremer III in Iraq. Current U.S. Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, who is also protected by Blackwater, said he had gone to the morgue to view the men's bodies, asserting the circumstances of their deaths were unclear because of "the fog of war."

Bush made no mention of the downing of the helicopter during his State of the Union speech. But he did address the very issue that has made the war's privatization a linchpin of his Iraq policy — the need for more troops. The president called on Congress to authorize an increase of about 92,000 active-duty troops over the next five years. He then slipped in a mention of a major initiative that would represent a significant development in the U.S. disaster response/reconstruction/war machine: a Civilian Reserve Corps.

"Such a corps would function much like our military Reserve. It would ease the burden on the armed forces by allowing us to hire civilians with critical skills to serve on missions abroad when America needs them," Bush declared. This is precisely what the administration has already done, largely behind the backs of the American people and with little congressional input, with its revolution in military affairs. Bush and his political allies are using taxpayer dollars to run an outsourcing laboratory. Iraq is its Frankenstein monster.

Already, private contractors constitute the second-largest "force" in Iraq. At last count, there were about 100,000 contractors in Iraq, of which 48,000 work as private soldiers, according to a Government Accountability Office report. These soldiers have operated with almost no oversight or effective legal constraints and are an undeclared expansion of the scope of the occupation. Many of these contractors make up to $1,000 a day, far more than active-duty soldiers. What's more, these forces are politically expedient, as contractor deaths go uncounted in the official toll.

The president's proposed Civilian Reserve Corps was not his idea alone. A privatized version of it was floated two years ago by Erik Prince, the secretive, mega-millionaire, conservative owner of Blackwater USA and a man who for years has served as the Pied Piper of a campaign to repackage mercenaries as legitimate forces. In early 2005, Prince — a major bankroller of the president and his allies — pitched the idea at a military conference of a "contractor brigade" to supplement the official military. "There's consternation in the [Pentagon] about increasing the permanent size of the Army," Prince declared. Officials "want to add 30,000 people, and they talked about costs of anywhere from $3.6 billion to $4 billion to do that. Well, by my math, that comes out to about $135,000 per soldier." He added: "We could do it certainly cheaper."

And Prince is not just a man with an idea; he is a man with his own army. Blackwater began in 1996 with a private military training camp "to fulfill the anticipated demand for government outsourcing." Today, its contacts run from deep inside the military and intelligence agencies to the upper echelons of the White House. It has secured a status as the elite Praetorian Guard for the global war on terror, with the largest private military base in the world, a fleet of 20 aircraft and 20,000 soldiers at the ready.

From Iraq and Afghanistan to the hurricane-ravaged streets of New Orleans to meetings with Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger about responding to disasters in California, Blackwater now envisions itself as the FedEx of defense and homeland security operations. Such power in the hands of one company, run by a neo-crusader bankroller of the president, embodies the "military-industrial complex" President Eisenhower warned against in 1961.

Further privatizing the country's war machine — or inventing new back doors for military expansion with fancy names like the Civilian Reserve Corps — will represent a devastating blow to the future of American democracy.

Los Angeles Times